I think about product and how one should approach product development a lot - I will use this post as a means of trying to distill my thoughts into (somewhat) comprehendible string of words, borrowing mathematical formalisms when appropriate.

The most important thing I’ve learned about product is that most ideas of the form “if we do \(x\), then \(y\) can do \(z\)” are wrong. They may seem valuable, useful, doable, etc. at first, but after varying degrees of investigation, one by one, they fall apart. This is mainly because in the real world, it is extremely hard to formulate what the correct \(x\) is based on the \(z\)’s you’d like to observe, as your dynamics model for how \(y\) perceives \(x\)’s and reacts to them is based on limited data at best and intuition at worst. Since the 3-dimensional space of all such possible 3-tuples is extremely large, it is almost guaranteed that your first choice of \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) will be sub-optimal.

However, a few of these ideas (3-tuples) actually have the potential of being valuable, meaning they lie in the neighborhood of another point \((x', y', z')\) that in fact does satisfy your theory. But finding this optimal point from the former will take a number of iterations in which you allow test \(y\) subjects to interact with test \(x\)’s and observing the dynamics, allowing you to iteratively refine your idea (as well as your dynamics model so that over time it improves as a means to simulate the real world).

In this setting, your job as a PM is to:

1) Empower your team, and yourself to generate many ideas \((X_i, Y_i, Z_i)\).

2) Continually build a robust dynamics model that with few false negatives, identifies promising candidate ideas.

3) Build a development culture and set of processes that let you apply hierarchical tests to further prune the set of potential ideas until you are left with a few validated ideas that you’ll ship.

Let’s go over how to do each of these.

1) Idea Generation

My idea generation framework is deeply influenced by thinking of Deepmind founder, Demis Hassabis, on creativity.

We can roughly break down new ideas to three buckets: More, Better, and New.

More

This is where most new ideas fall. “More ideas,” at their core, allow the user to do something that they can’t do today. They are centered around extending the functionality of the product, incrementally adding features or knobs that previously did not exist. More ideas are every PM’s worst nightmare because they incrementally add complexity to the product surface, often without contributing meaningfully to the product’s core value proposition.

About half of the requests received from customers are More ideas of the form “Can you add \(x\) so that \(y\) can do \(z\).” It is extremely important that a PM is disciplined about how she prioritizes amongst More ideas and which she actually incorporates into the product, because there is effectively an endless sea of these “feature requests” that without strict prioritization, the development team can end up building nothing but these incremental features.

Better

These ideas are centered around improving the product by working orthogonally to the product surface. They don’t add or update features, but improve the experience that a set of features enables across the board. The trivial example of this is speed improvements, security enhancements, UI design system overhaul, etc. Some “Better” ideas are explicitly visible and disruptive to the end-user while others are transparent and mostly concerning internal infrastructure. They usually require a large amount of work because they stretch across the entire (or large parts of the) product. “Better” ideas are instrumental in providing step-function changes in your metrics.

New

New ideas are usually a result of completely out-of-the box thinking and challenging a core assumption in the product’s definition. A mathematical analogy would be if the current product surface is some proper subset of the subspace \(S \subset \mathbb{R}^n\), then More ideas allow us to cover more points in \(S\), while Better ideas allow us to explore \(S\)’s orthogonal complement \(S^\perp\), exploring ideas that expand or contract the surface in a systematic way. In this framework, New ideas amount to extending the definition of \(S\) to one that is a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^m\) usually with \(m>n\) (though sometimes the opposite can happen, beautifully simplifying the product), thereby allowing the space to span points previously out of reach. This process also redefines every point in the current definition with its image point in \(R^m\), using some transformation \(T\) that actually does the mapping of points in the old space to the new one. In fact, the difficulty of finding the \(T\) is one reason why executing on New ideas is incredibly hard; concretely, breaking an assumption that allows you to define your product in \(R^{m}\) instead of \(R^n\) opens the door for new possibilities, but it will require you to redefine every bit of your product in this new world, with a new perspective and new terms. This is incredibly hard and if not dealt with methodically, will result in the new product to have “legacy features” that only make sense when thought about in the context of the old world in \(\mathbb{R}^n\)

Almost all “New” ideas are huge projects and sometimes fundamental shifts in the product strategy so careful deliberation is of utmost importance. New ideas can enable a brand new user persona, a brand new problem to be solved via the product or a brand new way that the team (and eventually the user) can think about the problem space the product aims to solve. The resolution of the definition of “New” ideas is usually low, because they describe interactions that are not well understood by the current dynamics system, so it’s important to note and validate all new assumptions that they bring.

2) The Great Filter

I would argue, this is the process that distinguishes good product teams from phenomenal ones. If you have creative, talented people, you will have no shortage of great More, Better and New ideas. Without a robust and effective process that filters, you may:

i) Waste time testing ideas whose flaws you should have noticed a priori

ii) Miss out on testing out promising ideas due to constrained bandwidth

iii) Worst of all, fail to incentivize and reward your teams’ creativity and investment in the product by failing to show them how and why their ideas succeeded or failed.

So how do you build this great filter?

A Detour on Strategy

First, let’s take a practical approach: why do we care about filtering the generated ideas? Because presumably, we believe there exist a set of delta’s, \(\Delta\), to our current product definition such that if incorporated, the net effect on the product’s metrics is positive. Some subset of the ideas generated will yield changes aligned with that delta, but most will yield deltas in other directions. To optimize for ROI, we would like to test and execute only on the ideas whose effect is expected to be largest and aligned with the deltas we would like to observe.

This may be an odd way of framing the problem. Why are we first fixing \(\Delta\) and then looking to see how the intended effects of any given idea align with it? I agree, this is odd; but this is how businesses work :)

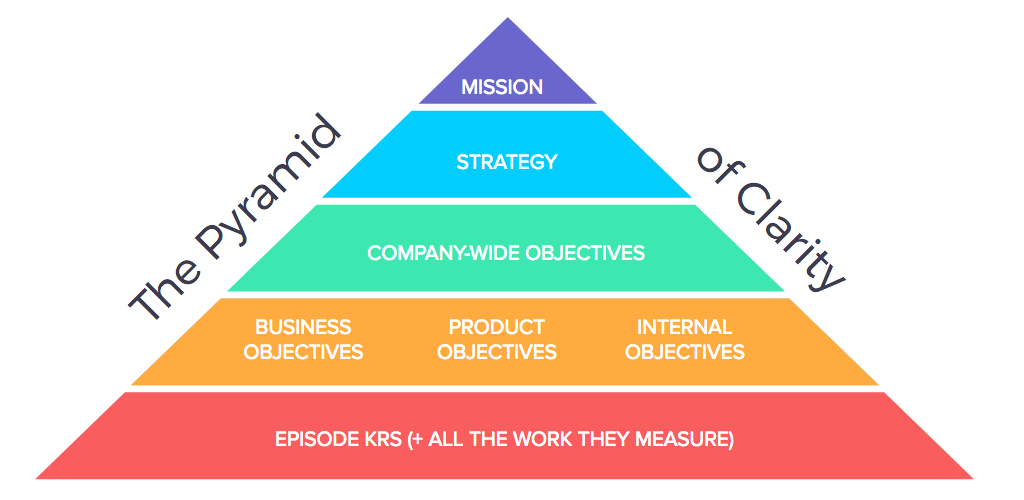

In less technical terms, usually, businesses have a hierarchical model for defining strategy and product roadmap, illustrated below.

This specific pyramid is one that the Asana product team uses, but every business has an equivalent. It starts with the company mission at the top, which hopefully changes extremely infrequently, if ever. Below the mission sits the competitive strategy that enables the organization to achieve this mission, providing guidance to what the organization’s ideal positioning should be in the competitive landscape, which product areas it makes sense for them to invest in, what M&A activity they should be open to, and many more high-level strategic questions and answers.

Below the strategy sits the first tangible abstraction: Objectives. These are usually annual or bi-annual goals that the entire organization wants to achieve. They are usually somewhat-scoped, targetted formulations of aspects of the strategy. The objectives are broken down into more fine-grained, well-defined objectives that are owned by specific functions, or teams. This is where things start to become concrete, with accountability and tracking. Objectives set at this level are usually SMART: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Timely. These objectives are broken down to Key Results by individual owners or owner teams. The separation between the objective, the key results that work towards the objective, and the specific tasks that deliver the key results is an important aspect of how modern organizations enable autonomous decision making and give individual teams the freedom to creatively solve problems.

Back to the Great Filter

So what did we learn in this detour? The key takeaway is that the \(\Delta\) introduced by an idea is most valuable when it moves the needle on an important KR, which belongs to an important objective, which is a critical part of the overall strategy. This framing gives us a way to reason about the relative worth of an idea. In other words, a naive algorithm for filtering ideas is to approximate their impact on product and business metrics, assess how vital those metrics are to the overall strategy, and test the top \(k\) ideas that have the highest impact to cost of test ratio.

If we take this formulation seriously, notice what a difficult job this filtering is; in order to create a filtering algorithm we have to:

- Break the product and business down to a number of key metrics or KPIs, \(M\)

- For each idea, \(I_i\), come up with a probabilistic model of how it will move any given metric in time: \(\Pi_{t}(I_i, M_j)\)

- Choose a timeframe \(T\) of interest over which to do the benefit calculation: \(\Pi_T(I_i, M_j) = \sum_{t \in (0,T)}(\Pi_t(I_i, M_j))\)

- Somehow be able to relate impact of different metrics to one another to come up with a total impact of an idea over its lifetime: \(\Pi_T(I_i) = \sum_{t \in (0,T)} \sum_{j}f((\Pi(I_i, M_j)))\)

- Finally, for any idea, there are many different tests we can run, at different resolutions, that may reduce the variance in our probability model to various degress. So we have to a) come up with the cost to variance-reduction curve, and pick the optimal point, for some notion of optimality.

Needless to say, no one in their right mind, actually implements this process; I just wanted to describe it in what I think of as its purest form for us to develop an appreciation for how difficult of a task this is. So how does one solve this challenge practically?

Generally, an idea is centered around a problem, with an opinionated way of solving it. For any idea, you should assess the following:

- Value of the problem: Is this solving a real, important problem?

- Usability of solution: Is our solution what users want to use to solve the problem?

- Feasibility of solution: Can we reasonably build and support the solution?

- Viability of problem and solution: Can we build a sustainable business around offering the solution to this problem

Most PMs focus on a subset of this list: if you’re a technical PM, you probably care about #1 and #3, a design-oriented PM (eg. product excellence PMs) will focus on #2 and a market-oriented PM will likely be consumed by #1 and #4.

As a PM, building the intuition that allows you to answer these four questions for any given idea is one of the most valuable investments you could make. Invariably, there will be a set of ideas that you will have low-confidence scores for, and that’s what you will need real user testing (next section) for; but the hope is that over time, as you refine your intuition, that set will continue to shrink. Think of your brain as a simulation environment where you can cheaply play out scenarios and estimate high-probability outcomes; the best of PMs have an internal simulation environment that closely matches the real world.

3) Discovery

Ideas that reach the third stage are ones that you have not been able to invalidate using previously seen evidence and reasoning. At this stage, you take a pre-trimmed set of hypotheses out of your lab (or office) and do some real testing.

I refer to this stage as Discovery because the point is not to answer “Which of these ideas are good enough for me to build?” If you frame it that way, you will always be able to convince yourself that some of them are good enough to warrant shipping. Ideas are like cattle; there are tons of them, and you must not spend significant effort into an individual one. What is more important than testing your idea is refining the model that should have been able to tell you whether this is a good idea or not.

In fact this phase is called Discovery because you are seeking to discover which parts of your dynamics model of the world needs to be improved. You are seeking to learn something new about the world in which your product operates so that the next time you have an idea that resembles the one you’re currently testing, your dynamics model will immediately scream with the right answer (“Definitely build this” or “no this is a waste of time”). As a by-product of this process, every once in a while, you will get an idea that does pass every test you throw it at and thus is deemed worth shipping.

So, in this discovery process, you will iteratively conduct more and more expensive test that aim to:

A) Iterate on the idea to make it more appealing (moving it closer and closer to \((x', y', z')\))

B) More importantly, port your learnings back to your dynamics model to make your learnings eternal

How you go through the Discovery process for a given idea is dependent on the idea, product and user. It could span anything from doing 1:1 interviews (common for B2B products) to user study tests using low-fi and high-fi mocks, to fake door tests, to dark launches to Early Access Programs to many more. The point is to hone in on the axes of the idea that are generating the most amout of uncertainty (variance) and design tests that will validate some hypotheses over these dimensions.

Practical Tools

Everything in this guide has been markedly abstract. While this is by design, I would like to close out by giving some example artifacts that implement some of the ideas that I’m talking about here.

The dynamics model I make a few references to is most puzzling. Of course, a formal mathematical function that takes an idea (as a delta to current product definition), and outputs its impact on the product and business would be ideal; however, this is usually infeasible. I approximate this function using two main artifacts: 1) A key metrics document and 2) A prioritized CUJ index.

Key Metrics

Whenever I start on a new team, one of the first things I do is draft up an original document that seeks to capture every important measure and metric the product, service or business cares about. I usually ground the structure of my metrics using the HEART (Happiness, Engagement, Adoption, Retention, Task success) for products and SUPER (Supportability, Usability, Productivity, Engagement, Revenue) for services. This allows us to have structure for listing what metrics matter for what reason to the business.

Prioritized CUJ Index

Critical User Journeys are instrumental in understanding how users interact with the product and which are the surfaces to be careful about changing. A prioritized CUJ index is a list of CUJs that you have identified and prioritized based on the above metrics. Mapping CUJs to metrics is not always trivial, which is why the prioritization of CUJs can take anything between a month to a year depending on how mature, large and structured a product is. It requires a lot of careful research and study of your users; but once it’s in place, it allows everything else to become much easier.

For example, it can easily satisfy the function of a dynamics model: for any given idea, you run through each CUJ, noting how the changed product will affect the CUJ and in which direction. After doing this for all CUJs, and by taking into account the priority of the CUJ, you have an estimate of the net effect of the idea on the usability of your product. You then add the new CUJs that it would enable and their perceived value (by again, mapping the enabled CUJ to a metric and backing out a priority for the CUJ).

In an ideal case, we would also add a regularization term that discourages adding new CUJs - because all else constant, more CUJs means a more complicated product, which is to be avoided.